Jane Beitler, NSIDC

Technology has made storing and accessing data and information easy, we think. Capture it, like a photograph or a series of weather measurements, then save it to digital storage housed in a safe place. Keep it cool and dry. Then it will be there for future generations to access and learn from. However, this is simply storage—like putting your grandfather’s old diaries, clothing, photographs, and mementos in a trunk. Preserving knowledge—what all that stuff meant and what it tells us about that past life—is a much more active, ongoing process, starting with understanding what you have and caring for it in a disciplined way. Can technology help with curation, and not just storage?

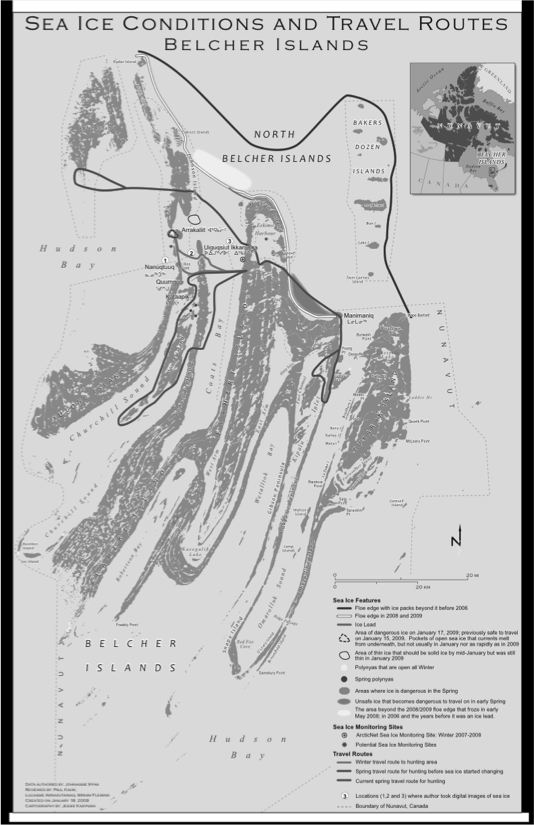

Figure 1. This map of sea ice conditions and travel routes resulted from an ELOKA interview with a hunter in the Inuit hamlet Sanikiluaq. The hunter created a map overlay depicting travel experiences and observations of the ice around the Belcher Islands.

Recently, the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA) project at NSIDC moved to adopt a system from The Data Conservancy that will help ELOKA curate the results of knowledge documentation projects carried out in Arctic communities. As part of a comprehensive data curation service at NSIDC, an instance of The Data Conservancy solution will provide needed tools for curating the diverse kinds of data, information, and knowledge that constitutes each Arctic community’s observations and knowledge.

ELOKA was launched during the 2007-2009 International Polar Year, a coordinated, collaborative effort to research the polar regions, to provide data management services and support to Arctic communities and others who are working with local and traditional knowledge (LTK) or who are gathering community-based monitoring data and information. The Sanikiluaq Sea Ice Project is typical of the collections housed by ELOKA. Sanikiluaq is an Inuit hamlet located on the Belcher Islands in southeastern Hudson Bay. Residents rely primarily on subsistence hunting for food, clothing, and other necessary supplies. Hunters draw on traditional knowledge of the environment to find animals and navigate around the islands.

Figure 2. The red box on this map of the Canadian territory of Nunavut indicates the Belcher Islands, where Sanikiluaq is located.

However, conditions in Hudson Bay have become less stable over the past few decades. Sea ice conditions are not as predictable, water currents are no longer reliable, and even the quality and condition of the animals has deteriorated at times. Wanting to document these environmental changes, Sanikiluaq chose ELOKA to support their efforts. The Sanikiluaq Environmental Committee began conducting surveys and gathering observations. Through a series of interviews, three hunters provided information and maps about changing conditions around the islands. Original data and information were provided as map overlays and base maps, video interviews, and photographs, with topics ranging from, climate and weather changes, changes in sea ice formation, travel safety, and changes in animal health and behavior.

Just what activities and challenges does curating this knowledge involve? While ELOKA is distinct in its focus on local and traditional knowledge, and each ELOKA community has unique sets of knowledge and requirements, the needs of Sanikiluaq are still typical in many ways. To begin with, the data and information need a stable place to reside, with organized and supported data curation practices, and skilled people to curate the data. NSIDC, a research data center at the University of Colorado Boulder, provides that institutional background, along with the specific financial support of the ELOKA project.

Those skilled curators in turn need technologies and tools. For example, a data curation system helps curators keep watch on the status of holdings, ensuring that objects are not deteriorating and that data remain uncorrupted.

Data and information also need a means to be accessed by present and future users. This involves not just systems, but active, thoughtful work by people. Curators can add value by recognizing, for example that a hunting community’s knowledge of sea ice conditions for travel may also be useful to a climate scientist’s interest in sea ice conditions as a climate indicator. Tools to support cross-cutting queries like this also add value by enhancing usability and accessibility of information. In many data repositories, queries can be limited by the perspectives and vocabularies of the original data contributors.

Initiating data curation services from scratch, however, can be a daunting task. Infrastructures for research data curation are still in their infancy, as are service models for digital data resources. While NSIDC already had the systems and people to manage an active archive of Earth science data, it too needed broader and long-term curation capabilities, as well as a system that was flexible enough to serve many disciplines and forms of knowledge.

Figure 3. Hunter Johnassie Ippak shared his sea ice observations as part of the Sanikiluaq Sea Ice Project. Photo credit: Chris McNeave

To support ELOKA’s requirements, NSIDC is implementing an instance of The Data Conservancy solution. The implementation includes both technical tools and organizational services for data collection, curation, management, storage, preservation, and sharing. Its underlying data model is flexible enough to accommodate the unique needs of an ELOKA community as well as other scientific disciplines. It can be scaled up to work with large collections, or it can work effectively with smaller ones such as the Sanikiluaq community. The system includes data preservation and storage, as well as the means to support curation across disciplines and diverse objects, such as maps, photographs, video, or samples, as well as digital data.

While comparable to institutional repository systems and disciplinary data repositories in some aspects, the DC Instance has capabilities beyond what those can provide, including a data-centric architecture, discipline-agnostic data model, and a data integration framework that facilitates cross-cutting queries. In particular, the Feature Extraction Framework (FEF) represents a unique, novel approach to atomizing data into constituent components that be indexed for queries or mapped to metadata elements. The DC Instance can fit into existing infrastructures, because it leverages established standards and tools, including the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) reference model and the Fedora Commons Repository Software, and provides Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to allow interoperability with other technical tools.

The ELOKA communities serve as an example of the versatility of the Data Conservancy solution. At the same time, ELOKA expands the use of Data Conservancy beyond university or government-based scientific research data to other forms of knowledge. The NSIDC implementation for the ELOKA project will provide feedback into the Data Conservancy blueprint and inform future capability development. Other Data Conservancy instances currently support scientific data, and also serve as the data archive solution at Johns Hopkins University.

The Data Conservancy is supported by a community of university libraries, national data centers, national research labs and information science research and education programs. It is led by The Sheridan Libraries at Johns Hopkins University. ELOKA is supported by the National Science Foundation. For more information, visit the Data Conservancy at dataconservancy.org. For more information on ELOKA’s use of the Data Conservancy instance at NSIDC, contact Ruth Duerr at rduerr@nsidc.org.